Kritiken (540)

The War Game (1966) (Fernsehfilm)

What is a film genre, or rather any other conceptual category that is supposed to allow us to facilitate the understanding of the world? In any case, something that is meant to have only an auxiliary function and to be discarded once it is revealed that the subject of investigation restricts and distorts rather than helps to clarify. The same applies to the "documentary" genre - although I would not attach too much importance to it, for example, here on FilmBooster, the documentary genre is not mentioned for this film. So, what is it then? I leave the invention of this new film category to film scholars, but its formulation is a necessity in the 21st century, as today, only a metaphysicist can work with the dichotomy of "objective reality" vs. "fiction." This is also evident in Watkins' case - the hypothetical "objective" (because it is based on government regulations, decrees, etc.) reconstruction gradually transforms into a fictional (because it never happened) story (and it is a story, after all, because the author is fabricating it!). Yet even that is not a completely imaginary story - it is a logically consistent imagining of that truly objective reconstruction. Moreover, Watkins also obviously manipulates the emotions of the viewer (for example, his attacks against the Anglican Church are completely arbitrary, although accurate), and he does so in a predetermined direction - an "objective documentary" should not do this, as the "facts" in it should speak for themselves. It requires inventing a new category, a new genre that will cover what is fictional in a documentary and vice versa, what is objectively/materially real in fiction.

Éden et après, L' (1970)

Perfect forethought in both the representation of the subject and, above all, in the completely conscious approach to the techniques of its representation. Metafictional methods and games with the functions of time and narration are not arbitrary allusions in Robbe-Grillet's works but rather a deliberate and inseparable part of the story itself, which irreversibly changes its essence. Example: when, during the opening credits, a voice-over utters a series of abstract words and verbal metaphors, we automatically begin to piece together these fragments into more coherent ideas, seeking connections between them and their meaning, etc. Throughout the film, these abstract words transform into actual events of the story, and verbal metaphors are replaced by visual metaphors and psychoanalytic/surrealistic symbols. In this way, the director has already provided us with the main components of the plot and their explanation in the introduction. However, this does not mean that we have been given the key to understanding the film - because, a) we only understand this during the course of the film, b) in the meantime, we are compelled to constantly contemplate the relationship between these inadequate pieces of information and the current plot, and finally c) we may reflect on the relationship between verbal representation and visual representation. There is certainly also a d), and e) – therein lies the beauty of it). Another example: symbolic compositions simultaneously split into general statements about the nature of desire and violence, comment on, or even anticipate the progression of the plot (when we see a blindfolded woman locked in a cage, it is both a reference to blinding and enslaving human desire and a foreshadowing of the future of the main character, who shortly thereafter ends up imprisoned with her eyes bound...). The main point is that the viewer never knows whether they are witnessing the course of the plot, a flashforward, a general symbol, a mere editing trick, or a character's imagination (which may later turn out to be the character's past and future). This could go on indefinitely…

Es ist schwer, ein Gott zu sein (2013)

1) Mise-en-scène. It is necessary to remember the true origin of this word - in the original term "mise en scène," which literally means "placing" "on" "the stage," i.e., placing objects and characters on that part of the theater boards or space in front of the camera that will be a substitute for the world for the following few minutes, and a substitute that is all the more believable the better you are able to arrange those objects. German demonstrated his genius precisely in how he was able to densify, shape, and make this film mise-en-scène perfectly plastic and tangible, and thus his entire fictional world. Just as a visitor to the Hermitage marvels at how every section of the palace halls is decorated with ornaments and gilding, here one marvels at how every corner of the imaginary space is filled with dirt, mud, decaying wood, and decaying people. 2) Camera. This time, German, as one of the greatest poets of the film camera, lent his services to the mise-en-scène, and his detailed and intimate shots allow the audience to almost touch everything that created the world of the planet Arkanar for three hours, and thanks to it and the mise-en-scène, the entire world of the audience. 3) Synthesis. A film about the dilemma of uninvolved observation versus participatory co-responsibility thanks to the camera, mise-en-scène, and resignation from narrating the plot, which would divert the viewer's attention from the proximity of all the dirt and mud of Arkanar, truly allows this dilemma to be experienced. It is because of all these techniques that the viewer experiences exactly what the main character undergoes, i.e., being irreversibly and fatefully drawn into a foreign world, be it another planet or the fictional world of the film.

O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (1968)

A unique synthesis of high and low, nihilistic, satirical, and ironic towards everything and everyone. It is one of the founding films of the so-called marginal cinema, a purely Brazilian category of films on the border between (deliberate) ignoble and underground. Similarly, this film, which is primarily an anarchic burlesque, playing in a free-thinking and unrestrained way with form and content, to which nothing is sacred, situates itself on the edge of pop art and avant-garde. It mocks (just like the entire marginal cinema "movement") the left-wing intellectualism and snobbery of the legendary Cinema Novo, as well as the police, criminals, and terror to guerrilla and army or officers, which only shows that, unlike its purely commercial Western counterparts, this film is not a genre film for its own sake, but with its undisciplined nihilism, it is an authentic statement by a 21-year-old director about the state of his country - after all, the country was ruled by a military junta since 1964, and by the end of the 60s, the country slowly but surely found itself in the midst of political violence of state and guerrilla terror. But what primarily attracts attention is the form, which, with its deliberately (but thoughtfully) chaotic combination of two main storylines, a barrage of editing combining various visual and sound sources (fictional story, fragments from period films, music from classics to contemporary pop, fake TV shows, etc.), and comedic coloring, creates a film that is, especially for foreigners, a unique, although of course highly subjective, source for understanding the reality of Brazil at that time. It is precisely the unusual combination of image and sound of the film that gives it a new dimension and, above all, new meanings, mostly of a cynical and humorous nature. /// Despite its irony and self-irony, the film is truly a smart testimony of the social situation at that time - the feared bandit who asks "Who am I?" throughout the film is ultimately shown as a powerless, uncertain, and insignificant person-symptom of a society that projects its own fears onto him like a projection screen (communists see in him "a man from the highest stage of capitalism," while right-wingers see him as a criminal and terrorist who takes from the rich and gives to the poor), and the ending shows how the all-powerful bandit is just a temporary affair in a time of the country's descent into unnecessary violence on a much larger scale.

Tiresia (2003)

I wanted to build on Lacan’s idea that the phallic signifier is also a symbol of desire, and furthermore, due to the fundamental impossibility of attaining desire, it actually represents the missing phallus, which does not mean it is completely absent. It is possible (and necessary) to represent it but in a veiled, hidden way. In "Écrits," Lacan writes that a woman who would attach an artificial penis under her clothes would arouse desire in all men. But what if that woman does not have to attach anything? The first half of the film directly invites psychoanalytic speculation, but the second half is fundamentally different and elevates the whole film to the realm of an updated ancient (see the mythological theme) allegory. Within this framework, we no longer move in the spheres of the mundane human psyche but in the spheres "between heaven and earth," which subverts the meaning of the previous half to a considerable extent. However, only to a considerable extent, because Bonello ultimately manages to connect both parts through the screenplay. It is definitely a thought-provoking film: besides describing the relationship between a person and what both attracts and endangers them existentially and identity-wise, in both the first and second halves where the male character is always exposed to the danger of losing his life (1st man) or livelihood (the priest to whom the oracle is a rival) and the loss of certainty about their own/possibly conformingly heterosexual, etc. / self, the film also poses an unsettling thesis for a white heterosexual European. After all, the carrier of a deeper relationship with the world and other people is the transsexual prostitute, who is also an illegal immigrant from a developing country!

Der plötzliche Reichtum der armen Leute von Kombach (1971) (Fernsehfilm)

1) "For centuries held in deep ignorance, they were unable to see the true cause of their suffering." However, not even the omniscient narrator can answer the true cause - only the film itself can: the true tragedy of peasants is not their material poverty, but their wretched imagination, which only enables them to identify with the "ideals" of their enemies, i.e., the rich and the masters. The touching effort of suddenly wealthy people to behave like nobility is not only the source of their inability to escape the world in which they live and truly change it, and thus their lives as well, but also the cause of their downfall. U. Sinclair provided a similar example in "The Jungle" (1906): the main protagonist (a poor worker) acquires a hundred-dollar bill, but how is he to use it? When he attempts to do so, he ends up at the police station because a poor person with money is suspicious in and of itself. From this, two lessons emerge: you have to be wealthy in order to steal even more (let us remember the recent economic crisis), and above all: a poor person will never find happiness if they only reproduce the lifestyle and mindset of the ruling elites. The same illusion appears in the attempt to escape to the USA (a low-tax haven both today and in the 19th century!) - this illusion stems from the same distorted imagination as outlined above. /// 2) Even if the viewer has not yet recognized the author's commentary on the contemporary/current social situation in it, everything changes with reflection on the musical accompaniment - the interchange of positions between the historical narrative and contemporary music establishes a scathing analogy between the past and the present.

Mujô (1970)

Although it may not be immediately evident primarily due to the incest theme, the real main characters are the young nihilist Masao and his spiritual adversary, but also his alter ego, the monk Ogino. The whole film is built on the contrast between these characters - a film about breaking conventions in behavior and imagination - in which the final confrontation between the two rivals is the true culmination and enlightenment for the viewer. In this aspect, the film is most interesting - its (I do not know to what disturbing extent, I do not know Japan) attack on religion, in which the worship of Buddhist symbols is revealed as bowing to one's own suppressed and hidden desires (often quite perverse even in the purest individuals, as shown by the plotline with the sculptor of sacred statues). The sacred spaces (the monastery, the place with the most beautiful incestuous moments) and objects (statues) are precisely the signs, symbols, and signifiers of this desire that, by their own nature as untouchably pure (physically and mentally) objects, they have to conceal. Yet as we can see, they cannot do it completely, and then we can see two strategies for dealing with life's uncertainty arising from this fact: either conscious cynicism like Masao or as a cowardly monk, literally futilely fleeing from awareness of his own desire, and therefore weakness, which he tried to suppress by escaping into social and religious conventions. /// The film is also very distinct in its formal aspects, especially with the camera - it utilizes almost all the techniques from the cameraman's catalog at that time.

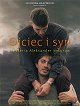

Vater und Sohn (2003)

The expression "spiritual incest" is accurate, but we can go further and ask ourselves - why, when we watch two half-naked men in a tight embrace, when we see their silent loving looks through detailed shots and reverse shots, why, when the whole film is bathed in soft sunlight and toned with warm colors like a Paraguayan soap opera, why, when lyrical music by the famous Russian homosexual Tchaikovsky plays (and Sokurov hits us directly over the head with this information), why are we not willing to imagine what we would automatically imagine in any other relationship? Why do we not perceive the relationship between these two characters as homosexual, even though they exist in a purely masculine world (the very few female characters are always symbolically and physically separated from the male characters - like the son's girlfriend/through a window, balcony/) and, not knowing the film's title or overhearing how they address each other, we would see them as members of a sexual minority? In the film, those who want to can perceive it as an intimate human drama or as a cinematic play with the cultural and social expectations of the audience, which, for civilizational reasons, prevent us from deducing an otherwise logical plot culmination and evoke unpleasant feelings with the return of suppressed psychological forces.

Vollmondnächte (1984)

The oldest filmmaker of the New Wave guard was also the most politically conservative and the most conservative when it came to films. While others focused more on film, Rohmer was more theatrical - all of his films that I have seen so far were built on the foundations of intelligent and internally elaborate dialogues, which, along with very subtle changes in character behavior, push the plot forward. The film form always takes a back seat. Even in this film, if there were just a few more ellipses during transitions from one apartment (set) to another, one could instead speak of a theatrical production than a film in all its aspects. Moreover, this conservatism has another aspect - Rohmer's stories are timeless in certain ways. Their plots could take place at any time, and they explore human relationships more from within than from the outside (but, of course, it cannot be said that the exterior is not reflected at all because the demeanor of the female protagonist of this film would still have been shocking a quarter of a century ago). In any case, nothing other than the search for timelessness in human behavior can result from the transposition of old folk proverbs to the 20th century... In summary, those who seek a detailed portrayal of nuances of the human psyche will get a multi-layered and clever "film," while those who seek a film without quotation marks will tend to get a multi-layered and clever film production.

La Lune avec les dents (1967)

The French New Wave in the francophone part of Switzerland and, above all, a film about rebellion. The minimalist plot and runtime, with slightly experimental and quite ironic elements, conceal an intentionally illogical story about a rebel that encompasses protest on several levels - from left-wing critique of the wealthy bourgeois society, through a wannabe American punk with a leather jacket and sunglasses, to a torn poet with a world-weary sense for interesting metaphors. The whole film plays out in an ironic spirit (which does not exclude appropriate and serious observations about the world), but above all, it is ironic in its narrative structure in that at the end, it literally plays with its characters and with the prejudices of the audience. It is precisely through this self-reflection that the film approaches (the half-Swiss) Godard, and if we use his early filmography (which Soutter undoubtedly drew inspiration from) for a concise summary of this film, we can say that The Moon by Our Teeth is a combination of Breathless, Band of Outsiders, and Le Petit Soldat.